|

Alaska Natives are the indigenous peoples of Alaska. They include: Aleut, Inuit, Tlingit, Haida, Tsimshian, Eyak, and a number of Northern Athabasca cultures. Alaskan natives in Alaska number about 119,241 (as of the 2000 census). There are 229 federally recognized Alaskan villages and five unrecognized Tlingit Alaskan Indian tribes.

The Tlingit and Haida are more similar to Indians along the coast of present day British Columbia than to other Alaskan groups. The Tlingit occupied the vast majority of the area from Yakutat Bay to Portland Canal while the Kaigani Haida, whose Haida relatives occupied the Queen Charlotte Island off the north coast of British Columbia, controlled the southern half of the Prince of Wales archipelago. The two groups share similar social and cultural patterns; however, their languages are unrelated and they have distinct ethnic identities.

The Haida were neighbors of the Eyak, Tlingit, and Tsimshian, and these four tribes often intermarried and their clan systems had counterparts in the other surrounding tribes. The Haida have two moieties, the Eagle and Raven, and also have many clans under each moiety. Like the Eyak, they have an exogamous matrilineal clan system. Each of these tribal groups spoke a different language not understood by the others. The Haida people speak Haida, an isolate language, (not related to any other language group), with three dialects: Skidegate and Masset in British Columbia, Canada and the Kaigani dialect of Alaska.

The original homeland of the Haida people is the Queen Charlotte Islands in British Columbia, Canada. Prior to contact with Europeans, a group migrated north to the Prince of Wales Island area within Alaska. This group is known as the “Kaigani” or Alaska Haidas. Today, the Kaigani Haida live mainly in two villages, Kasaan and the consolidated village of Hydaburg. The Haida are master canoe makers, constructing their canoes from cedar logs up to 60 feet in length.

Haidas in the United States do not have reservations. Like most Alaska Natives, they live in a Native village instead, which is called Hydaburg. The Haidas lived in rectangular cedar-plank houses with bark roofs. Usually these houses were large (up to 100 feet long) and each one housed several families from the same clan (as many as 50 people.)

Alaska Native villages do not have the same sovereignty rights that Indian nations in other US states do, but the Haidas belong to a coalition called the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska which handles tribal government on behalf of several Native villages. The Haidas of Hydaburg also have a local council that has economic control over their village and its resources.

Haida women gathered plants and herbs, wove baskets and cloth, and did most of the child care and cooking. Men were fishermen and hunters and sometimes went to war to protect their families. Both genders took part in storytelling, artwork and music, and traditional medicine. The Haida chief was always a man, but women held important roles as clan leaders.

The Haida, Tlingit, and Tsimshian seem to show greater adaptability to civilization and to display less religious conservatism than many of the tribes farther south. They are generally regarded as superior to them by the white settlers, and they certainly showed themselves such in war and in the arts.

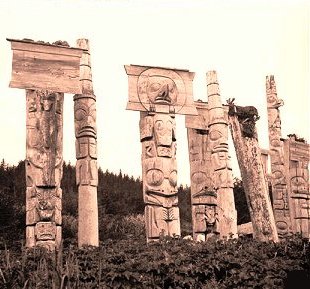

Of all peoples of the north west coast the Haida were the best carvers, painters, and canoe and house builders, and they still earn considerable money by selling carved objects of wood and slate to traders and tourists. Standing in the tribe depended more on the possession of property than on ability in war, so that considerable interchange of goods took place and the people became sharp traders.

The Haida fashioned for themselves a world of costumes and adornments, tools and structures, with spiritual dimensions appropriate to each. The decorations on the objects they created were statements of social identity, or reminders of rights and prerogatives bestowed on their ancestors by supernatural beings, or of lessons taught to them through mythic encounters with the animals, birds, fish or other beings whose likenesses were embodied in the crests passed down through generations.

|